First-year writing courses through the University of Connecticut have six essential components that undergird the entire class: (1) course inquiry; (2) field research; (3) studio pedagogy; (4) multimodal composition; (5) information, digital, and media literacy; and (6) reflective writing. Over the last few blog posts, we’ve been assessing how Gholdy Muhammad’s four aspects of historically responsive literacy can engage in feedback and the habits of practice. For this blog post, we’ll be considering Muhammad’s fifth aspect, joy, developed in her book Unearthing Joy, in relation to each of the essential components and how they might be used to create a joyful experience in the writing classroom.

First-year writing courses through the University of Connecticut have six essential components that undergird the entire class: (1) course inquiry; (2) field research; (3) studio pedagogy; (4) multimodal composition; (5) information, digital, and media literacy; and (6) reflective writing. Over the last few blog posts, we’ve been assessing how Gholdy Muhammad’s four aspects of historically responsive literacy can engage in feedback and the habits of practice. For this blog post, we’ll be considering Muhammad’s fifth aspect, joy, developed in her book Unearthing Joy, in relation to each of the essential components and how they might be used to create a joyful experience in the writing classroom.

For Muhammad, joy is not simply happiness or a rush of endorphins; joy is uplifting “beauty, aesthetics, truth, ease, wonder, [and] wellness,” forming “solutions to the problems of the world,” and finding “personal fulfillment” (Introduction). A fun classroom can be a part of bringing in the aspect of joy, but the real work of joy comes in developing purpose and passion. In the writing classroom, this could mean encouraging students to form a relationship with writing that shows them how it can affect the world around them and their own selves.

Joy in Inquiry

Course inquiries guide each version of first-year writing, giving enough railing for students to be pointed in the right direction but also enough room for the students to guide their personal inquiries and learning. In the baseline syllabus for the Storrs campus, the collective inquiry is, “What does an education do?” For the semester, readings and discussions are based around education, but each student develops their own questions and lines of inquiry in relation to the class’s guiding question (or questions). “What does an education do?” is broad enough that it can expand to fit each student’s questions.

Students can find joy in inquiry by discovering their own passions and interests. The inquiry is meant to allow a student to follow their own wonder, developing their writing projects as answers to their own questions. With the educational inquiry, for example, a student who is passionate about mental health might lead out in asking questions about mental health in education and how it can be improved, while a student who is passionate about sports and fitness might use their writing and research to uncover ways of integrating fitness more into the classroom. In this way, all the students are learning about education and what it does, but they are pursuing their own inquiries. This solo pursuit supporting a group inquiry creates an atmosphere of finding joy in discovery—whether that discovery is your own answers or someone else’s in the classroom.

Additionally, a collective inquiry for the course allows students to discover alongside each other new voices and projects that are pursuing similar work, if perhaps at a scale larger than the course itself. As students dive into the archive, read up on their chosen inquiry, and learn new things, they find joy in finding out that they can put their voice alongside the voice of those in a chosen scholarly field and those in the classroom around them. Inquiries—both individual and collective—mean that knowledge is growing within the classroom atmosphere and with those in the discipline.

Joy in Field Research

First-year writing is meant to support students developing a wide range of skills that allow them to practice the philosophies and methodologies forwarded in discovering, learning, and researching. It is meant to help students think about how to solve problems and develop their writing on their own. A lot of answers can come from books and articles, but answering questions sometimes requires more than just reading. Sometimes it requires students to do field research.

Field research develops different approaches to questions and finding answers. While the skills of close reading (or listening) and good note-taking are important to field research, field research also encourages students to think critically in the moment. If, for example, you have a project built on the Humans of Education project, in which students interview people in the field and discover what their opinions are, the students will discover that they have to think quickly in the moment of the interview—especially when the person doesn’t provide a lot of in-depth information that can be collected and curated into the final project. This quick-thinking can bring joy in a student’s work because they’re having to stay engaged in the conversation and not lose any threads of thought while talking. Juggling between the different ideas that must happen when performing field research adds a purpose to the execution of this essential component.

Joyful Studio Pedagogies

Studio pedagogy is meant to be fun! It encourages creativity and messiness and messing up and doing things wrong and failing and also winning and finishing and being proud of making. All of these things can evoke joy in our classroom. By getting messy—from using glue sticks and poster board to remixing work through Canva or Adobe Express—students engage in “active and accessible learning, play, design, and digital literacies.” But even more, they get to see what’s possible and how they can all find different ways of sharing ideas and finding those ideas in what their peers make. Joy in studio pedagogy also comes from engaging in projects as a group, developing talents alongside each other and seeing how other people think.

Joyful Multimodal Compositions

Students participate in multimodality on a daily basis. As they scroll through social media, walk around a grocery store, or watch a television show, they are experiencing multimodal compositions. Multimodal composition reflects how the world around us has changed from one in which we get information from ink and paper to one in which we learn and communicate through small rectangular black boxes that bring video, images, and sound to the palm of our hands. Being able to participate—even make a change through—this method of communication and interaction is an important part of multimodal composition; it’s meant to not only ask students to think outside the box but also to analyze and rhetorically understand outside the box too.

Joy in Information, Digital, and Media Literacy

While information, digital, and media literacy is about learning the skill of navigating the library system, it’s also about learning how to assess and understand what is being presented to us in our information overload society. How does one take time out of their scrolling to answer the age-old question, “Why”? This form of literacy teaches the skills of academic research—diving into library databases, grasping how to read an academic article, and developing an approach to learning more about an article’s research genealogy. It also helps students form a deeper understanding of what they are consuming—from TikTok videos to informational YouTube videos to Instagram posts to news articles—and how to learn more. This exploration can bring joy into the classroom by exciting students about different ideas that are all around them.

Reflective Writing for Joy

Reflective writing can be used in many parts of the first-year writing classroom—from self-assessment of an assignment to preparing thoughts for a discussion to starting a writing assignment. Self-assessment reflective writing can be a way for students to find joy by discovering a truth about their own writing process. When students engage in reflective writing to help them prepare their thoughts for a classroom discussion, they are untethered from having to have a clear, coherent, and polished presentation and can engage in the joyful process of wondering and exploring ideas.

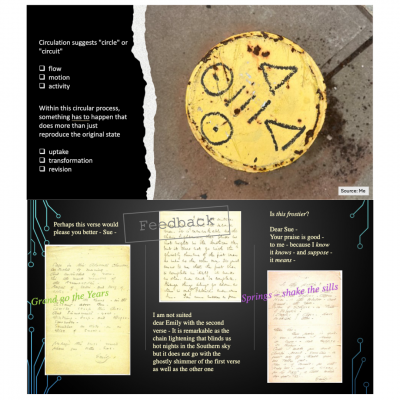

Throughout various sessions, presenters, educators, and scholars brought forward stimulating examples and approaches to integrate circulation into writing pedagogy. Scott and Tom, in their welcoming remarks engaged with

Throughout various sessions, presenters, educators, and scholars brought forward stimulating examples and approaches to integrate circulation into writing pedagogy. Scott and Tom, in their welcoming remarks engaged with  The

The  Circulation as Rhetorical Context

Circulation as Rhetorical Context Circulation for Brainstorming and Ideation

Circulation for Brainstorming and Ideation

First-year writing courses through the University of Connecticut have

First-year writing courses through the University of Connecticut have