In late June, we had our first ECE English Summer Institute, a kind of 3-day seminar with a wonderful group of about 20 teachers of FYW courses. Our theme was “Composing Environments for Teaching and Writing,” which meant, in part, a focus on interrelationships between writing and our interaction with specific, local environments. We read a lot about assemblage and assemblage theory (two different things, really), and we thought about how our writing courses might make more use of our interactions with the non-human world and the understanding we gain by collecting, sorting, and assembling objects.

Because I had just a day earlier moved into my very first house, I made a lot of comments about “stuff” and its impact on my current mindset—“Do we really need all these books?” or “Does that pipe in the basement look right?” And, drawing on Jody Shipka’s words about the importance of cultivating a collector’s mindset, Anne (my wife) joked that she’s not a hoarder, she’s “enchanted by the world.” And, yes, if setting up a home is itself a kind of composition, a bringing together of already existing elements into a new space, we have—in bags and boxes in the attic, garage, and basement—resources.

In teaching composition, we sometimes overvalue clean, finite order or the “clarity of thought” that is clear because it is so abstract, so theoretical. Especially early in a writing course, and especially early in a student’s college career, it seems worthwhile to foster creativity, spontaneity, and a sense of the inexhaustible qualities of composition by asking students to be collectors and gatherers, to interact with their environment in exploratory ways and in ways that do not resolve to the simplification of “finding evidence.” Asking students to engage in what Shipka calls “rigorous-productive play” means valuing the work of writing down, photographing, recording, transcribing, interviewing, and juxtaposing.

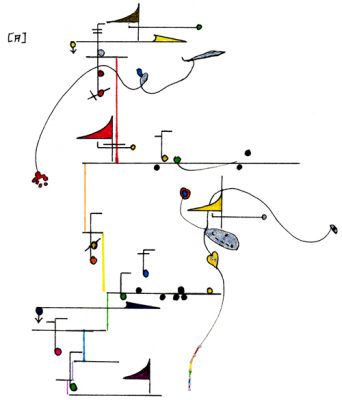

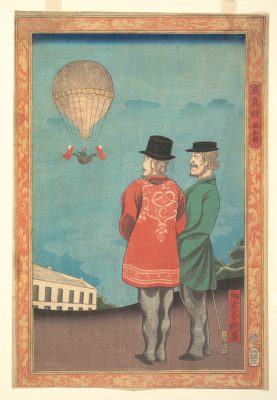

At our new campus in downtown Hartford, we are experimenting with our new site as a resource for writing. We’ve borrowed some ideas about place-based learning from our neighbor, Capital Community College, and we’re encouraging students to consider the areas just beyond the campus, which include city streets, public buildings, historic structures, parks, cemeteries, a very complex mix of human beings, and so much more. If we want to be on the nose, we can even walk across the street to the Wadsworth Atheneum (free to students and UConn faculty) and gaze directly at a Joseph Cornell box. Enchanted, indeed.

If the individual writers in our courses gather materials from their wanderings, we can, from there, collaborate and invent through writing and composition that engages with this collection. That is, it might be wise to forestall exact matching of purpose (what’s your thesis?) with the work/play of discovery. To me, the FYW seminar shouldn’t be a course in how to write, which poses the real work of writing as a technical matter. It should rather be a course in helping students learn to have something to say, an investigation into writing as relationship, negotiation. When we place value on the collecting and gathering of materials for conversation and writing, we put students in a position to show us something and begin the process of dialogue through writing.

Work Cited

Shipka, Jody. “To Gather, Assemble, and Display: Composition as [Re]Collection.” Assembling

Composition, edited by Kathleen Blake Yancey and Stephen J. McElroy, NCTE, 2017, pp. 143-160.

I like to kick the tires of the FYW courses, looking for places that might need reinforcement or further thought. One soft spot I am always noticing in my own courses is my delivery on the promise that the writing we do in the class is not just a performance of competence or a simulacrum of engagement that effectively goes nowhere, what I refer to as “writing for the teacher.” I do act on this promise. Each new iteration of my FYW courses pushes further toward more circulation of student work, more collaboration, and more focus on student-driven commentary. I see the FYW courses as essentially environments designed to feature and support communication by students to students. The writing seminar is most of all a place for students to see their writing, perhaps for the first time, as something purposeful and context-specific, designed for others’ use. As we explore—verbally and through drafts—our various interactive encounters with texts and ideas of others, we all learn from the discourse that begins to flow out of the course itself. And supplementing this work with a range of supporting articulations such as presentations, abstracts or introductory statements, and responses to other projects allows for further recognition that the learning in a writing seminar happens in this open exchange. For the most part, I am delighted by this evolution toward exchange that makes the other courses I teach (often content-driven literature courses) feel a little old-fashioned, wooden, unidirectional.

I like to kick the tires of the FYW courses, looking for places that might need reinforcement or further thought. One soft spot I am always noticing in my own courses is my delivery on the promise that the writing we do in the class is not just a performance of competence or a simulacrum of engagement that effectively goes nowhere, what I refer to as “writing for the teacher.” I do act on this promise. Each new iteration of my FYW courses pushes further toward more circulation of student work, more collaboration, and more focus on student-driven commentary. I see the FYW courses as essentially environments designed to feature and support communication by students to students. The writing seminar is most of all a place for students to see their writing, perhaps for the first time, as something purposeful and context-specific, designed for others’ use. As we explore—verbally and through drafts—our various interactive encounters with texts and ideas of others, we all learn from the discourse that begins to flow out of the course itself. And supplementing this work with a range of supporting articulations such as presentations, abstracts or introductory statements, and responses to other projects allows for further recognition that the learning in a writing seminar happens in this open exchange. For the most part, I am delighted by this evolution toward exchange that makes the other courses I teach (often content-driven literature courses) feel a little old-fashioned, wooden, unidirectional.