Earlier this month, Brandon Hurst and I (your ECE English Graduate Assistants), had the pleasure of witnessing the fruition of the work we did along with our leadership (Scott Campbell and Tom Doran ) and our Advisory Board during our conference: Collaborative Circulation: A Recursive Roadmap.

Throughout the day, our ECE English instructors delved deeply into the concept of “circulation” in the writing classroom. With a name like that, the conference itself was designed to be an expansive journey, one that would move beyond considering circulation as an endpoint. Our presenters and panels encouraged us to map the dynamic pathways that our ideas and written works follow as they flow through stages of ideation, creation, feedback, revision, and community engagement.

Each session, led by members of our Advisory Board highlighted how circulation can be seen not only as a process of sharing and re-sharing work but as a collaborative venture that involves early ideation, rhetorical context, and multifaceted feedback. Circulation became more than the final stage of the writing process. Instead, we explored it as a living and recursive part of the writing process, one that shapes our work from the first spark of an idea to its permeation within a community.

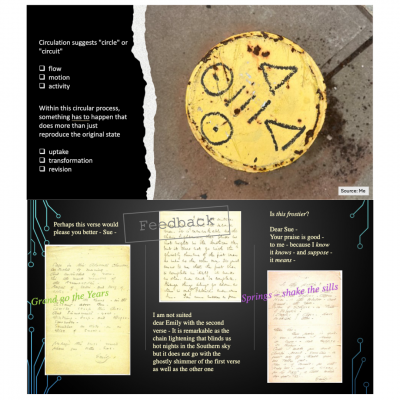

Throughout various sessions, presenters, educators, and scholars brought forward stimulating examples and approaches to integrate circulation into writing pedagogy. Scott and Tom, in their welcoming remarks engaged with circulation in graffiti tagging and the poems of Emily Dickinson, respectively. Attendees were sent off to their sessions primed for the opportunities that the exploration of the vast uses that centering circulation in our writing process reveals and the growth for students that that engenders. We examined traditional notions of circulation as “publishing” but pushed past that view to consider circulation as a transformative process that writers and students experience in iterative, often unpredictable ways. A recurring theme was the collaborative nature of circulation, with presenters sharing how they encourage students to engage with peers, instructors, and outside communities, making the writing process more transparent and connected.

Throughout various sessions, presenters, educators, and scholars brought forward stimulating examples and approaches to integrate circulation into writing pedagogy. Scott and Tom, in their welcoming remarks engaged with circulation in graffiti tagging and the poems of Emily Dickinson, respectively. Attendees were sent off to their sessions primed for the opportunities that the exploration of the vast uses that centering circulation in our writing process reveals and the growth for students that that engenders. We examined traditional notions of circulation as “publishing” but pushed past that view to consider circulation as a transformative process that writers and students experience in iterative, often unpredictable ways. A recurring theme was the collaborative nature of circulation, with presenters sharing how they encourage students to engage with peers, instructors, and outside communities, making the writing process more transparent and connected.

The Circulation for Brainstorming and Ideation session looked at circulation in its ideation phase. Throughout the conference, this session became a wellspring of ideas and conversations through Post-It notes as attendees engaged with images and responded to the sessions that came before. The ideas in circulation (on the notes) influenced those participating in the next session. In this way, the participants not only engaged with the materials provided by the workshop leaders, but also the responses that came before them. The session emphasized the recursive and collaborative nature of ideas in an engaging activity. You can see images of the compiled comments here.

Our Circulation of Feedback session focused on feedback loops within classroom settings, where the presenters emphasized the circulation of feedback as a dialogue and discussed methods for engaging students in a series of reciprocal exchanges that invite them to see their writing as a living piece on which to act upon and respond to. Such discussions underscored the importance of fostering a space where students can experience the full lifecycle of writing—a journey where texts evolve in relation to diverse voices and perspectives.

The Circulation as Rhetorical and Compositional Context session focused on how the rhetorical context in which the writing of students exists can move beyond the classroom. Using the Humans of Education project (renamed to Humans of East Lyme), One presenter shared how her students expand the reach of their writing by creating a new rhetorical context. Another presenter shared some great-looking posters that emerged from a class that had traced the social impacts of a song. The posters led back to a shared playlist of all the songs. Both of these assignments invite students and the community into the reading of these pieces and can be shared through time and space with tools like QR codes.

The Circulation as Rhetorical and Compositional Context session focused on how the rhetorical context in which the writing of students exists can move beyond the classroom. Using the Humans of Education project (renamed to Humans of East Lyme), One presenter shared how her students expand the reach of their writing by creating a new rhetorical context. Another presenter shared some great-looking posters that emerged from a class that had traced the social impacts of a song. The posters led back to a shared playlist of all the songs. Both of these assignments invite students and the community into the reading of these pieces and can be shared through time and space with tools like QR codes.

Brandon and I also hosted two hands on (and quite arts and crafty) sessions. In these sessions we used Where the Wild Things Are by Maurice Sendak and “Joy” by Langston Hughes to offer a new activity for students to engage with texts in multiple circulation phases. During the sessions all participants commented, had conversations through, deconstructed, and reconstructed texts to encapsulate and enact a tactile experience of circulation.

During our closing session, multiple cross-campus instructors shared with the conference attendees the diverse ways in which they are implementing circulating practices in their classrooms. We heard about audio postcards, civic engagement expos, judging texts already in circulation, the impetus we have to write (both in and out of the classroom), and the impact of circulation on identity construction.

As a newcomer to the ECE English world, I want to extend my gratitude to the presenters and attendees. The collaborative spirit among participants was palpable in the conversations that I engaged with and reminded me that, as educators, we can only benefit from sharing our challenges, successes, and strategies to nurture a richer, more meaningful writing experience for our students.

A special thanks must also go to the Advisory Board: Kevin Barbero, Kyle Candia-Bovi, Michael Ewing, Emily Genser, Siobhan Jurczyk, Alexa Kydd, Ramona Puchalski-Piretti, Kristen Rotherham, Arri Weeks, and Karen Tuthill-Jones. Their dedication to facilitating engaging, collaborative sessions, and ensuring that each participant’s voice was heard created a truly inclusive environment.

If you missed out on this conference or want to dive even deeper into these ideas, you can visit our Fall 2024 Conference Materials or our larger resource repository in our SharePoint site. I’m excited to share that we will hold our next conference in April in conjunction with the larger UConn FYW Program. Thank you, again, to everyone who made Collaborative Circulation: A Recursive Roadmap a success. I look forward to seeing you all in April!

Circulation as Rhetorical Context

Circulation as Rhetorical Context Circulation for Brainstorming and Ideation

Circulation for Brainstorming and Ideation