Let’s, for a moment, imagine a fairly typical nightmare scenario for a writing instructor: a sudden increase of class size to 50 students. Of course, many instructors already have 50 or more students in total, but I am talking about 50 in a single course. My goal here is not to advocate for such a system (!) but rather to consider how a more sudden quantitative shift might necessitate a significant rethinking of instructor work that might not otherwise happen through the steady drip, drip of small, incremental class size increases.

Our partners in other courses and departments have faced these numbers before, and the “solution” has often been to drastically curtail student productivity to that which can be sorted through standardized forms (like quizzes and tests) or truncated into a few minutes of discussion at the end of a lecture. Although most academics have, at fancy colleges or in graduate school, experienced (and now mourn the loss of) the seminar format, with its student-driven lines of inquiry and its long-form writing projects, the typical college course is still primarily modeled on content mastery that can be demonstrated through testing or in very formatted, conventional writing.

What I want to discuss here, instead, is an experiment with large-scale courses that might still be project-based and student-driven. Accepting that such a course can even be taught is a contentious, even obnoxious claim, perhaps, and, what’s worse, it can seem that I’m flirting with a model of teaching and learning that is complicit with the worst elements of educational corporatism. So, for the record, let me be perfectly clear: I think the ideal class size for writing course remains somewhere between 12 and 15. Within this range, you have enough voices to establish heterogeneity of outlook and experience, but you also have few enough projects to provide detailed feedback over many drafts. And, of course, you get to know students much more readily. A larger or much larger class size strains the capacity of an instructor to provide support for all students, and, in time, usually either necessitates a dismantling of the seminar model or unfairly impinges on the instructor.

But let’s get postprocess here and work within the constraints of our imagined situation. The class size question depends on an understanding that an instructor’s work is finite and that each added student subtracts from this finite sum. And, in terms of direct, one-to-one feedback, this is surely true. The pressure some teachers feel to live up to an often tacit but deeply felt standard of individualized feedback can be enormous. Too often, lengthy written comments on student drafts serve as markers of instructor diligence and time spent (see how much I cared about this one draft?) rather than an effective use of instructor time given the real conditions of many writing courses. So let’s exacerbate those conditions with our experiment with 50 students so that there can be no illusion that a modestly retooled pedagogy will work. What needs to happen, instead, is a remaking of student and faculty expectations for a writing course.

We can ward off that culture of guilt without capitulating to a model of standardized and rigid teaching and learning. But, to do so, we have to acknowledge that the courses themselves must change, and sometimes radically. Some of the things an instructor might need to do in this situation include:

- Break the expectation of instructor feedback as primary.

- Put responsibility on students to become readers of each other’s work. Sure, we already share drafts, but much more can be done to foster collaborative invention and response within the class itself.

- Put responsibility on students to co-author some projects. Consider class-wide composition.

- Design courses as environments for interconnectivity and creative composition rather than stages for performing a pre-existing repertoire of competencies.

- Introduce and develop key terms and concepts for reflecting on and learning from the composing that happens in the course.

- “Solve” the problem of audience by positing the class itself as an engine of both production and consumption. How are you contributing to the class conversation? How can you influence or change the people in the room through your work?

- Spend far more class time engaging with student work, openly and in detail. What do we have here? What’s possible here? What comes next?

- Save yourself from seeing a project in 100 versions. What a surprise to read a “final” project that isn’t something you’ve responded to before.

- Move the modes of communication toward audio or spoken feedback as well as alternative forms of visual feedback (up to, but not including, stickers (heh)).

- Ask students to become presenters and curators of their work, always situating larger projects alongside blurbs, introductory texts, working bibliographies, and brief presentations that help others see and anticipate these larger works. (Factor this assembling and presenting work into grades.)

- Use class time to develop and test provisional rubrics or evaluative criteria. What does successful work in this project do or look like?

- Give feedback that is not on a one-to-one ratio but which uses samples, excerpts, and volunteered student work.

- Use digital tools and spaces to more efficiently constellate and circulate student work.

- Use office hours or conference time for students who seek more individual feedback. (And lament the loss of more time per student.)

- Recognize that other colleagues who teach the other courses that students take have responsibility, too, for helping students become informed, generous, self-aware, and capable writers and communicators.

- Take note of what gets lost (and it is a LOT) in large courses, and advocate, when you can, for improvements and support.

You may have noticed that not much here is entirely new. What I’ve described is driven by a consideration of efficiencies, perhaps, but not all innovation must come from economic considerations. Critical pedagogy, for one example, has long advocated for the distribution of responsibility to all class members on democratic principles. Ecological composition asks us to design courses that make use of the affordances of place and technology. And multimodal composition reminds us that even academic communication need not always be lengthy prose paragraphs. Also, a lot of what is proposed here depends not only on instructors and students but on programs. If the goal of these innovations is to help writing teachers build what Byron Hawk calls “smarter environments,” the teachers themselves need to be working in a smarter environment, a site where implementing these changes is developed, modeled, and supported.

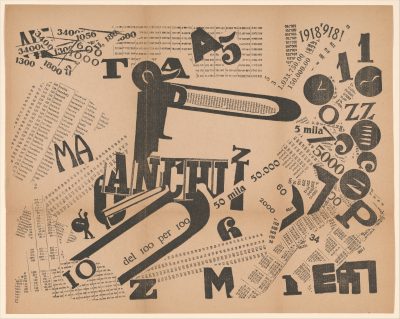

Nightmare scenario or vision of the future—tumultuous assembly or artmachine? What we know of the large class is that it is transformative. Now can the teaching we’ve been doing (and the programs we’ve been building) help us anticipate and engage with this transformation?