Here’s an easy question: If a math teacher teaches math, and a geography teacher teaches geography, what does a writing teacher teach?

Writing, obviously. Like I said, an easy question.

Or at least it seems easy until we consider it alongside another question: Does a math teacher teach math and does a geography teacher teach geography in the same way that a writing teacher teaches writing?

What does it mean to teach writing? A math teacher—we’ll just send our geography teacher to the capital of New Zealand for now—might have her students learn theorems and formulas. Is there an equivalent of theorems and formulas in ECE English classes? Should there be?

I would say that as writing instructors we do have some conceptual frameworks and sets of terminology that can play a role similar to the math teacher’s theorems and formulas. For example, ethos, logos, and pathos. Or the rhetorical triangle, to offer another example. A student can memorize and learn to use these conceptual frameworks in the same way that he can memorize and learn to use a2 + b2 = c2.

But writing isn’t algebra. It isn’t geometry. (It may be calculus, but let’s leave that idea for another post.) So what is the point of portable neat little concept-constellations like ethos, logos, pathos and writer, text, reader?

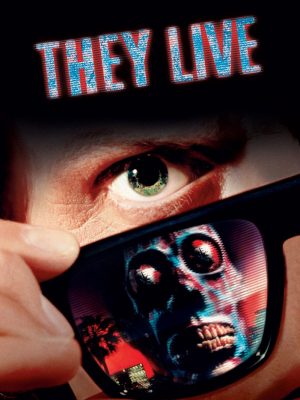

First, let me argue in favor of portable neat little concept-constellations. I like them a lot. As someone who thinks about writing often—and often has to discuss writing with other people—sets of terms like ethos, logos, pathos help me to recognize aspects of writing that I likely would not have noticed otherwise. It’s like putting on my ethos, logos, pathos glasses. When I wear them, I can see these different concepts in practice.

Sets of terms and conceptual frameworks aren’t just glasses. They’re also the elements of a language that allows me to discuss writing precisely with students and other instructors. Without this language, it would be difficult for me to offer useful feedback. It would be difficult for students to communicate with one another about their drafts or write reflectively about their writing.

But sometimes when I wear those glasses, the big plastic frames block certain areas of my vision even as the lenses help me to see other areas very clearly. If I never take them off, I may even forget that there’s much more to be seen than what is visible in my (admittedly sometimes very useful) EthosLogosPathos-Vision.

And sometimes when I speak my ethos, logos, pathos language, I suddenly find myself trying to express a concept for which the language has no word. But I’m so used to this language that I use to discuss writing—I think in it, I dream in it—I fool myself into thinking that it’s not the language that’s deficient but rather the inexpressible idea. So I push it away.

For these reasons, it’s important to treat our writing-related sets of terms and conceptual frameworks as tools. Depending on the particulars of a situation, a tool may be productive. But a hammer’s no help for cleaning glass. We have to remind ourselves and emphasize to our students (when we introduce them to these tools) that they aren’t always productive—in some cases, they may even be limiting. And when they do start to hinder how we think about writing, we have to be ready to cast them aside and engage openly and flexibly with a writing project.

It may be the same way in real-life math or geography. I don’t know. But that’s certainly not the case for my straw-person math teacher with her theorems and formulas. We do things differently than she does. And when it comes to the teaching of our straw-person geography teacher, we’re on a whole different continent.

—

For further (and less flippant) reading about possible roles for “content” in writing courses, I highly recommend Writing Across Contexts: Transfer, Composition, and Sites of Writing by Kathleen Blake Yancey, Liane Robertson, and Kara Taczak. (With your UConn credentials, you should have access to the book in PDF form through JSTOR.)

GREAT post, Erick! And I like the flippant–but serious too–tone of it as well. I’m also very fond of “portable neat little concept-constellations”–which is what I’ve always liked about RHETORIC (as an art, practice, theory).

Brenda B