About 18 students. Facing each other in pairs. Students leave cell phones in netting at front of room. Lots of physical support for the work of the course, including desks that are mobile, a pleasant room space, a crate for collecting work, the aforementioned netting, and a very wide range of images, texts, maps, signifiers on the walls—[the teacher’s] degrees and college info, some runners’ racing bibs, wigs and crowns (for dramatic performances), a whiteboard with today’s lesson, a map of Greece/Crete, and lots of photos of students. An enormous paper roll about three feet wide. [Update: yes, those are specially chosen curtains, too.]

One of the new, small traditions of ECE events is my sharing with Kim Shaker the title of a completely obscure but wonderful movie I’ve just seen. I’m a Filmstruck proselytizer, and I can’t help talking about, say, Vera Chytilova’s Daisies (wow, drop everything and watch this tonight) or The Lure (described on the site as a “genre-defying horror-musical mash-up…[which] follows a pair of carnivorous mermaid sisters drawn ashore to explore life on land in an alternate 1980s Poland“). Today I’ve got Agnes Varda’s Mur Murs on my mind. And, yes, it has something to do with teaching writing. I’ll get to that.

In the first part of my place-based 1010 course, we examined our campus buildings and grounds. What should an academic space be? was a key question driving our first projects. Also: Who is academic space for? With bell hooks’ essay, “Keeping Close to Home: Class and Education,” and a few other readings, we looked at our campus and explored hooks’ claim that education should be “the practice of freedom.” A frequent point that students made was that our clean, new spaces lacked a feeling of “home.” One student compiled images and descriptions of a student union space at CCSU that functions like a lodge or den, where students can be informal, eat, and watch television (her hierarchy of “freedoms,” not mine). But a second student was even more focused on classroom space, and she argued that the blank white walls of our classrooms communicated a cold, modular indifference to the character of the conversations and work going on in these spaces. She asked why her high school classrooms had been so wonderfully “homey” while the college rooms are so blank.

I had certainly noticed the difference between high school and college settings in my visits to various high schools. My epigraph describes just one of the high school classrooms I’ve visited recently that feels quite different from the arid “multipurpose” room I’ve documented in these photos. But I had never before considered how regional campus students—as commuters—share something significant with their high school counterparts: their sense of community, if they have one, largely comes from what happens in their academic spaces. Residential students at places like the Storrs campus have dorms and dining halls (and a lot more) to build community. (We are familiar with the trope of the college student decorating a dorm or even painting a rock to establish a sense of home or belonging.) I’m envious of the ways that high school teachers transform school spaces into worlds infused by contributions they and their students have made to the classes (so much posted student work!).

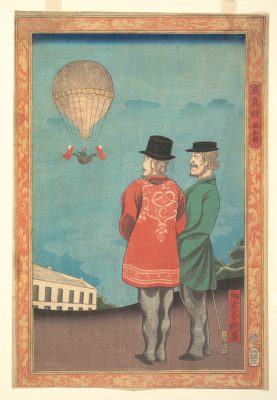

When Agnes Varda made Mur Murs, she was living away from home—in California, not France. And she was estranged from her husband. A companion film to her fictionalized, personal story in Documenteur, Mur Murs turns outward, to the stunning public murals painted throughout East Los Angeles. The paintings are massive and often magnificent; I can’t hope to describe them. Most feature people from the community, the artists in most cases overtly countering a feeling of being underrepresented in more conventional art. The murals reclaim and remake space. As Varda puts it, “in Los Angeles, I mostly saw walls—murals as living, breathing, seething walls. Murals as talking, wailing, murmuring walls.” Varda, we can see, finds solace and stimulation in these interactions. Her camera adds yet another layer of connection and documentation.

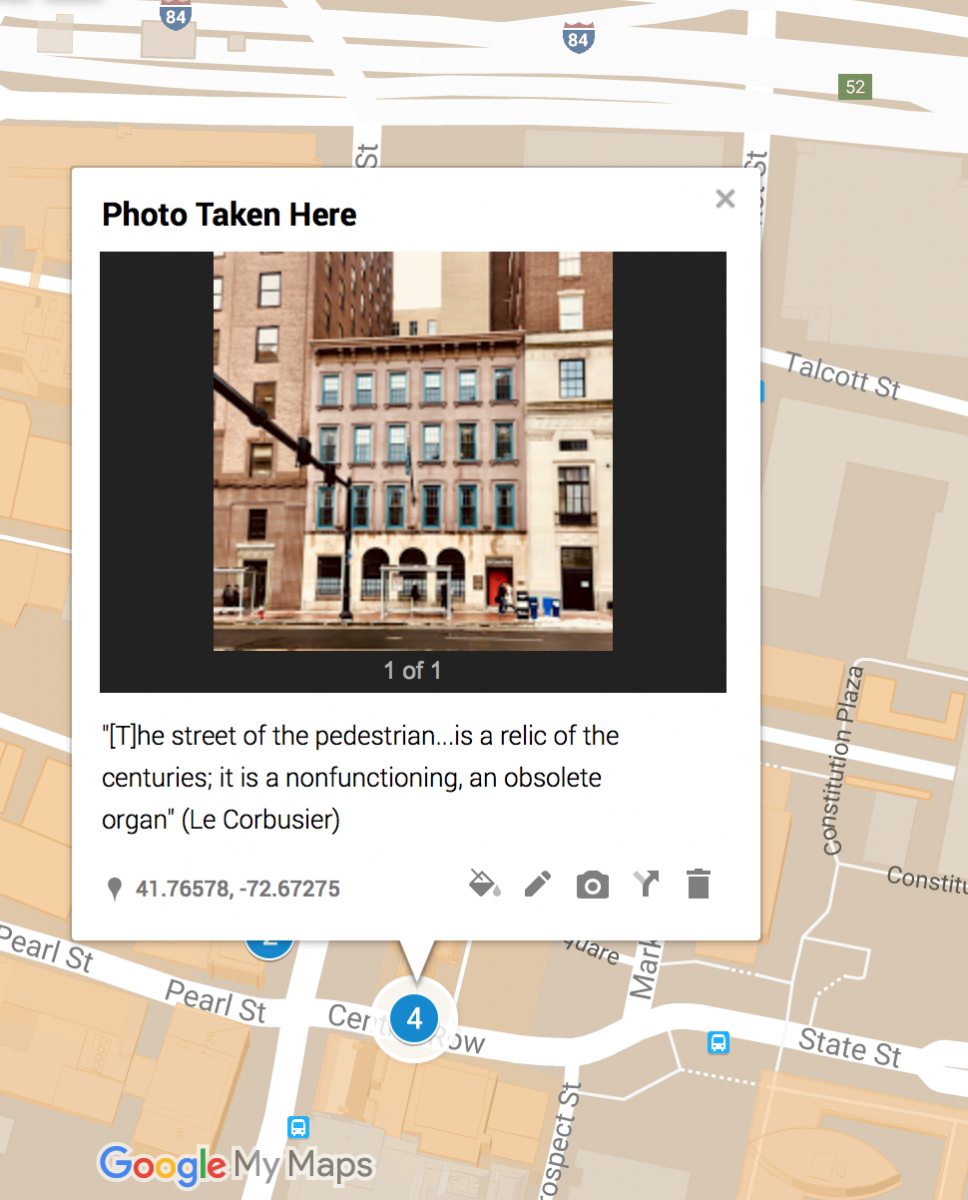

I’m not about to bring paint to my classroom. I don’t think a 100-foot collage of “the forgotten people” (striking workers, soldiers, nurses, etc.) would go over well with our campus administration. But I don’t think it’s too much of a stretch to see our courses as performing a similar kind of community building. To an extent, the work we’re doing in composition is a territorialization—of texts, of academic topics, and of spaces. And often multimodal composition makes this work of reclaiming and remaking more apparent. It was the photographing of our campus that led to these first thoughts. And now, deeper into the semester,

most days include time spent with students projecting work—often photos, maps, and sometimes drawings—onto these blank walls. One student has recently been photographing the tiny, stressed public library spaces in Hartford’s South End. Another has been showing us images of open space that has been fenced and padlocked. I show them a particular building that I photograph every day. The writing and conversations are better when we’ve populated our walls with images and texts that we’ve selected. It doesn’t last long, and the dazed look that students have when the lights come on isn’t entirely about adjustments to light. But it feels, too, like we’re getting past the blank page.

I like to kick the tires of the FYW courses, looking for places that might need reinforcement or further thought. One soft spot I am always noticing in my own courses is my delivery on the promise that the writing we do in the class is not just a performance of competence or a simulacrum of engagement that effectively goes nowhere, what I refer to as “writing for the teacher.” I do act on this promise. Each new iteration of my FYW courses pushes further toward more circulation of student work, more collaboration, and more focus on student-driven commentary. I see the FYW courses as essentially environments designed to feature and support communication by students to students. The writing seminar is most of all a place for students to see their writing, perhaps for the first time, as something purposeful and context-specific, designed for others’ use. As we explore—verbally and through drafts—our various interactive encounters with texts and ideas of others, we all learn from the discourse that begins to flow out of the course itself. And supplementing this work with a range of supporting articulations such as presentations, abstracts or introductory statements, and responses to other projects allows for further recognition that the learning in a writing seminar happens in this open exchange. For the most part, I am delighted by this evolution toward exchange that makes the other courses I teach (often content-driven literature courses) feel a little old-fashioned, wooden, unidirectional.

I like to kick the tires of the FYW courses, looking for places that might need reinforcement or further thought. One soft spot I am always noticing in my own courses is my delivery on the promise that the writing we do in the class is not just a performance of competence or a simulacrum of engagement that effectively goes nowhere, what I refer to as “writing for the teacher.” I do act on this promise. Each new iteration of my FYW courses pushes further toward more circulation of student work, more collaboration, and more focus on student-driven commentary. I see the FYW courses as essentially environments designed to feature and support communication by students to students. The writing seminar is most of all a place for students to see their writing, perhaps for the first time, as something purposeful and context-specific, designed for others’ use. As we explore—verbally and through drafts—our various interactive encounters with texts and ideas of others, we all learn from the discourse that begins to flow out of the course itself. And supplementing this work with a range of supporting articulations such as presentations, abstracts or introductory statements, and responses to other projects allows for further recognition that the learning in a writing seminar happens in this open exchange. For the most part, I am delighted by this evolution toward exchange that makes the other courses I teach (often content-driven literature courses) feel a little old-fashioned, wooden, unidirectional.