Reflections on Our October Conference

What is the relationship between critical thinking and the personal, between our contexts and the intellectual work we do in the writing classroom? Our conversations at our Fall ECE Conference often explored the kinds of writing we ask our students to do and the extent to which those arguments serve them in both their educations and, more broadly, in the development of their interactions with the world around them. In the morning session, we met as a large group to discuss small excerpts of student work taken out of context in order to talk about what we see happening in that work and how it makes us think more deeply about the ways we discuss the genres of our students’ work. As we went over these excerpts, we wrote anonymous responses in a web-based program, “Padlet,” regarding moments we found interesting and the audience and genre of each piece. Each of us could see each other’s responses as they came in. Part of the intention of recording these responses was to ask ourselves to think about the ways we read student writing and to reflect on the ways we write assignments.

In that spirit, then, there were a few trends that came from both these responses and from the conversations we had during the session itself: the common terms we use to categorize student writing, as well as the problems those categorizations pose for those of us who are both instructors of literature and of writing. A number of terms came up multiple times: analysis, synthesis, argument, academic (audience/argument), and lens. In some specific examples, there were times where people seemed to not only agree with one another but also take up their terms; when one or two people identified the genre of a piece as an op-ed, for example, many soon followed.

What might these terms tell us about our practices and the ways we read student work?

While some responses and terms varied throughout, there did seem to be a general, common vocabulary that we were drawing on. The linking of two texts, such as Rodriguez and Pratt’s “Arts of the Contact Zone,” we often identified as “synthesis.” While it may seem obvious to us, it seems worthwhile to then ask, what does “synthesis” mean? What is its rhetorical use in writing? How might it gesture at some sort of larger stakes beyond the boundaries of our assignments? Linking two texts together might allow us to discover something new or interesting about each piece, potentially, and this might be its value to us as instructors of literature. At the conference, however, we also asked how students might be able to connect to, or make use of, the texts by using them to talk about higher-stakes issues.

In other words, while we might value synthesis and close, sustained analysis, we can also frame synthesis and analysis as rhetorical tools that allow our students to critically engage with and explore complex ideas. How might an analysis of Slaughterhouse-Five allow our students to think more deeply about Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder? About the effects of war, and the role writing might play in speaking about or to those effects? Why might arguing that Rodriguez’s memoirs could, perhaps, be considered an autoethnography be something intriguing, inspiring, or exciting? We spent the end of the session thinking about how we can encourage our students to use the valuable things they notice in and across texts to address larger issues – such as, for example, asking students to compile an anthology of excerpts about World War II aimed at veterans and write an introduction to the anthology. What synthesis or analysis looks like will differ depending on the rhetorical particularities of the assignment and each student’s approach to it – in other words, their audiences, the medium, the mode, and their goals/purpose.

For those of us who are instructors of literature, we are, of course, invested deeply in the worth and value of literary texts. Many instructors also have to contend with having to fulfill a certain amount of content each academic year to ensure their students either meet curriculum guidelines and/or are prepared to take an AP test. At times, then, it becomes challenging to balance the demands of the content of the course (literary texts) and the deep work of writing that First-Year Writing courses prioritize. First-Year Writing asks students not to write about texts (whatever genre those texts may be), but rather, to engage deeply with and explore the practice of writing itself, to approach writing as a complex process through which we can encounter and expand on complex questions, particularly as First-Year Writing offers a groundwork of writing and critical thinking practices meant to be cross-disciplinary. If our students need to read Frankenstein, what kinds of questions about the world, various cultural assumptions (for example, regarding gender), scientific practices, etc. might they be able to write towards? What kinds of arguments is the novel making, and how might our students expand on them in new and interesting directions in their 21st century contexts? What kinds of writing can they do that might serve them broadly in future writing practices?

This kind of thinking, I’ve found, has also helped shape my approach to teaching content-based literature courses not housed under First-Year Writing. My initial approach asked what texts they would be expected to read, ensuring I was teaching what I was ‘supposed’ to. However, when I taught a survey course on Poetry, my class consisted of forty students, many of which were not majors. So I had to question my own assumptions about the role of the course. I not only asked, “what kinds of poems will they be expected to know?” but I also asked my students, “why are these the kinds of poems others will expect you to have read in a course on poetry?” Moreover, I asked them to consider the rhetorics of poetry – how it makes use of sound and space, how it both overlaps with and differs from various kinds of speaking, knowing, or writing, how it intervenes into larger cultural arguments. Literary texts don’t need to be static, and we can also address their historical contexts without also neglecting our very real, 21st century contexts at the same time, especially. We can also explore the ways all kinds of texts – literature, film, critical essays, websites, TV shows, etc. – engage their own kinds of rhetoric and composition, and how our students’ exploring those rhetorics can affect their own writing practices.

Several of the excerpts seemed to speak to audiences outside of the field of literary studies. Many found excerpt 2, a reflection on differing cultural practices surrounding food between the United States and China, “authentic” as opposed to other excerpts, although some felt it demonstrated a lot of bias. Similarly, excerpt 3, a strong statement against gender-coded graduation gowns, was seen as contributing to conversations beyond the more specific boundaries of academia or the classroom, but again, some found the tone overly contentious. We might ask ourselves how our students imagine themselves speaking to the outside world and what rhetorical choices they’re making; what sorts of discourses might they be drawing on or mirroring in writing these pieces? Both pieces included use of the first person; in excerpt 2, the student referred to themselves in order to make claims about their own culture. In excerpt 3, the student referred to a “We” in order to establish that they were referring to a whole community. I remember the first academic paper I wrote that sought to fill in what, to me, was a pretty big oversight in the conversation on a Renaissance poet’s work – I recently revived that piece in hopes of publishing it, and realized that I was performing the voice of scholars I had read, trying to match the perceived rhetorical situation of my argument. As a young scholar, even one in his MA, I drew on the tones of voice I was familiar with and attempted to imitate them, still trying to understand how differing rhetorical situations might my affect my writing. Students might be drawing on examples of the genre they’re writing in, ways they’ve heard others speak about similar topics, or their own understandings of how their audience expects them to respond (particularly if they believe their primary audience is us, their instructors).

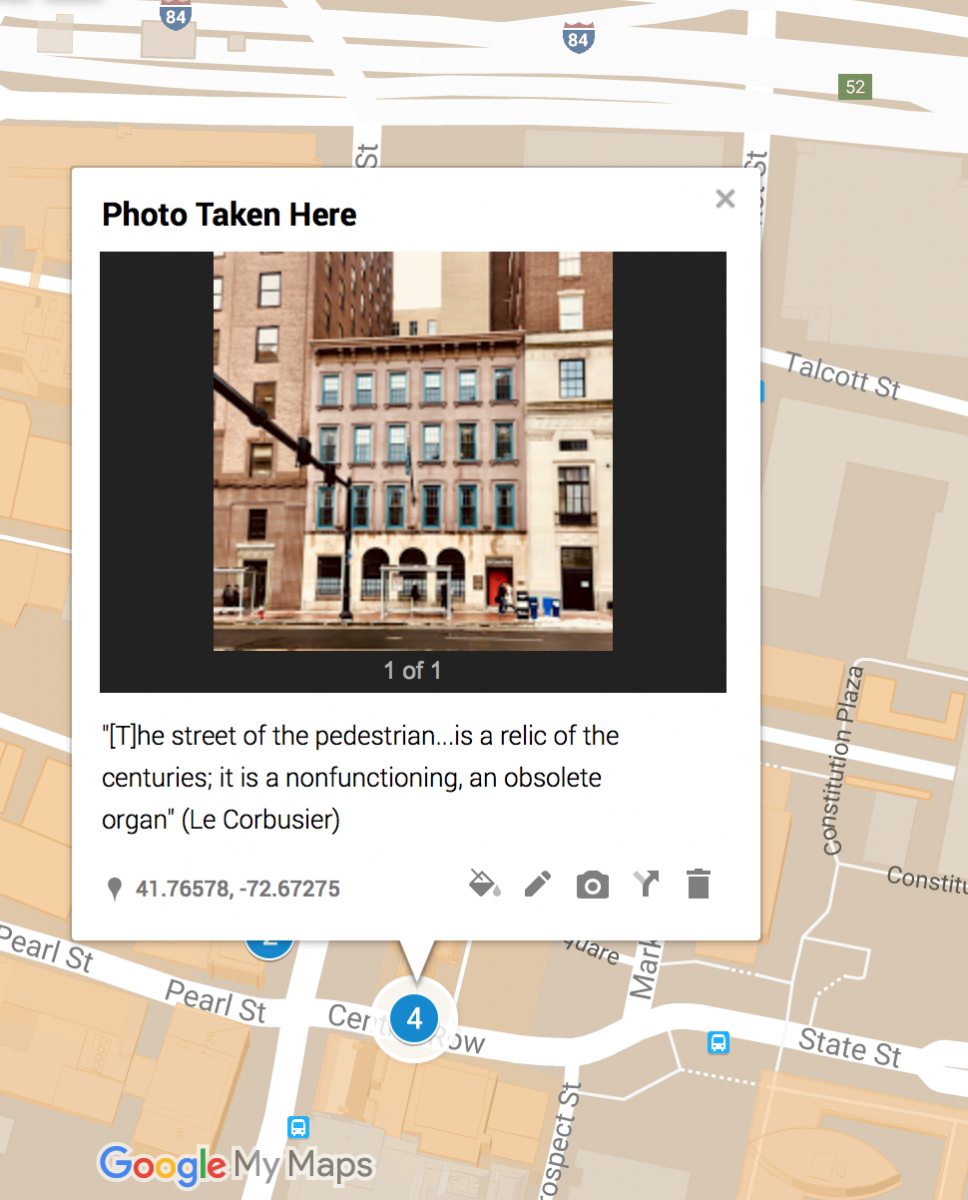

These students may indeed have been writing in their own voices, and many in the comments on excerpt 2 found it authentic, as I noted above. Nonetheless, these students’ rhetorical situations (both imagined and real) have led them to make certain choices about what they’re presenting, what contrasts they’re drawing, the way they engage with evidence, and what point they’re hoping to make (however we might evaluate the “success” of each student’s draft). We should question and critically think through our own assumptions about our students’ perceived rhetorical situations. Interestingly, for example, there were mixed responses to the fourth excerpt, a video essay taking up Baudrillard’s assertion that “the Gulf War did not take place” – perhaps since it was a video, the various references may have been difficult to catch, but many felt that it had the tone of a “conspiracy theory.” Perhaps it was something about the statement that “the Iraq War did not take place,” the use of images, and the calm tone of the student – either way, that the video was taking a complex idea from a text and using it to then explore a wider issue (the portrayal of war more generally in the media, and how this applied to the Iraq War specifically) was not generally accounted for. It seems crucial, then, to question our own assumptions about various modes of composition – if we assign our students to write an op-ed, why? What kinds of rhetorical moves will they practice, and how do we talk about them with our students? How will they build on a complex conversation? If we ask them to write a video essay, what are our assumptions about voice-over videos? How can we account for those assumptions as we write assignments?

These are all fruitful questions that have no definitive answers – but, as I balance writing an intensive literary dissertation on Romantic poetry and my work in the often separate field of Rhetoric and Composition and writing program development, they’ve proven particularly generative for me in the weeks since the conference. I hope that we can continue reflecting on these questions and practices moving forward.

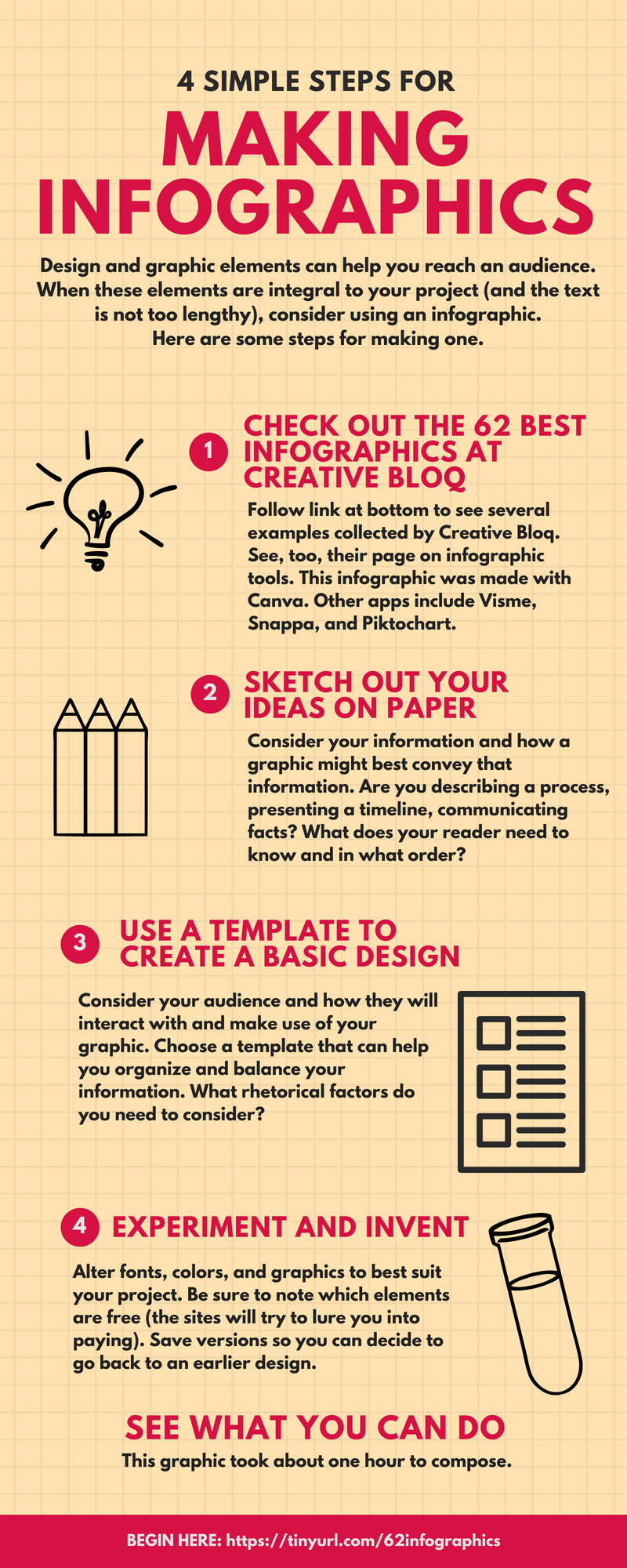

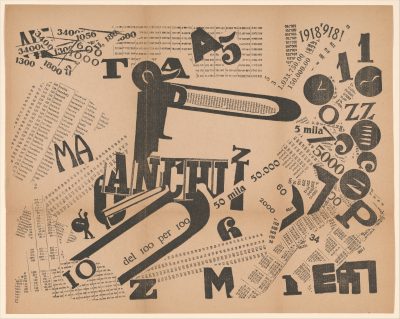

Sometimes my students will tell me I talk too fast. And they’re not wrong. Blame coffee, nerves, my many years spent in New Jersey and New York, or just my usual state of edgy excitement. For whatever reason, I get a high word per minute count when I am teaching. I can promise to try speaking with more measured, spondaic, or prosed deliberation. And yet—and there’s always an “and yet”—there’s something worth considering about the many ways we try to cheat the careful cadence of prepared discourse. In speaking, we often look for ways to thwart the simple left-to-right, top-to-bottom linearity of writing. In simple terms, I think we are looking for ways to say many things at once.

Sometimes my students will tell me I talk too fast. And they’re not wrong. Blame coffee, nerves, my many years spent in New Jersey and New York, or just my usual state of edgy excitement. For whatever reason, I get a high word per minute count when I am teaching. I can promise to try speaking with more measured, spondaic, or prosed deliberation. And yet—and there’s always an “and yet”—there’s something worth considering about the many ways we try to cheat the careful cadence of prepared discourse. In speaking, we often look for ways to thwart the simple left-to-right, top-to-bottom linearity of writing. In simple terms, I think we are looking for ways to say many things at once.