Scholarship as Impetus and Inspiration

Kari’s recent post on Felicia Rose Chavez’s The Anti-Racist Writing Workshop suggests ways to find texts and sources from beyond the usual, familiar anthologized or textbooked readings—those warhorses that appear so often in syllabi. My post explores another, perhaps unexpected, avenue for shaking things up, published academic texts. Specifically, my goal here is to remind you that some of the most interesting and powerful writing about topics taken up in FYW courses—identity, race, culture, power, gender, etc.—happens in journals and books that escape the notice of the more popular press and media coverage. If we’re looking for texts to provide an impetus for collaborative antiracist work, we might mine the resources that are right amid us. Choosing readings from these texts:

- provides models for students seeking to compose in academic modes (while also challenging the notion that there are static rules for academic writing)

- makes use of access enabled by university affiliation (many of these texts are not otherwise free or accessible)

- and gives students a taste of how antiracist work happens within the university and through its channels

Let’s take the example of Duke University Press and some of its recent publications in its African American Studies and Black Diaspora section, all of which are currently available as free downloadable PDFs through the UConn library. (Links may require sign in and some clicking through.) These texts are interdisciplinary, often multimodal, creative, well-researched, and critically engaged with the problems and possibilities of academic writing. In other words, they are great demonstrations of what can be done in academic settings. These are not easy texts; they invoke and develop theoretical terms and complex histories. But they remind me of the rich, challenging texts that have often served as cornerstones in FYW courses—texts to be worked on and revisited through the course. Here’s a sample:

Christina Sharpe’s In the Wake: On Blackness and Being is a powerful and poetic examination of Black life, an observation of the ongoing legacies of slavery through meditations on terms of sea travel. Chapters here are designated as “The Wake,” “The Ship,” “The Hold,” and “The Weather.” In a section called “How a Girl Becomes a Ship,” for example, Sharpe studies a photo of a young girl being evacuated in the aftermath of the earthquake in Haiti in 2010. The girl stares back at the photographer, and on her forehead, in English, is the work “Ship.” What is one to make of this cryptic detail? Sharpe’s analysis is less about solving the mystery than seeing this image as yet another example of Black lives caught within an ordering mechanism that seems to only see them when their worlds are falling apart. Sharpe’s development of what she calls “wake work” provides a tool for “how to live in the wake of slavery”: “[R]ather than seeking a resolution to blackness’s ongoing and irresolvable abjection, one might approach Black being in the wake as a form of consciousness” (14).

Christina Sharpe’s In the Wake: On Blackness and Being is a powerful and poetic examination of Black life, an observation of the ongoing legacies of slavery through meditations on terms of sea travel. Chapters here are designated as “The Wake,” “The Ship,” “The Hold,” and “The Weather.” In a section called “How a Girl Becomes a Ship,” for example, Sharpe studies a photo of a young girl being evacuated in the aftermath of the earthquake in Haiti in 2010. The girl stares back at the photographer, and on her forehead, in English, is the work “Ship.” What is one to make of this cryptic detail? Sharpe’s analysis is less about solving the mystery than seeing this image as yet another example of Black lives caught within an ordering mechanism that seems to only see them when their worlds are falling apart. Sharpe’s development of what she calls “wake work” provides a tool for “how to live in the wake of slavery”: “[R]ather than seeking a resolution to blackness’s ongoing and irresolvable abjection, one might approach Black being in the wake as a form of consciousness” (14).

Rinaldo Walcott’s The Long Emancipation: Moving Toward Black Freedom, indebted to Sharpe, distinguishes between freedom and emancipation, suggesting that emancipation is ongoing and incomplete, an unfolding process. I’m using two brief chapters from this book in an upcoming unit on funk in my 4000-level course, but I’ve used his article, “The Black Aquatic,” from the open access journal, liquid blackness, as a model for the kind of academic writing I want my students to attempt. That piece, which defines the Black aquatic as “Black peoples’ lived relation in and to bodies of water,” includes first-person writing, photos of the objects it examines (including a still from the film Moonlight and an image of a ship made into artwork), and stylish document design, including pull-quotes, two-column formatting, and bold use of color. We should be inviting students to produce more work that looks and feels like this.

Simone Browne’s Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness is a wonderful book I described at last fall’s conference. Browne takes us through both historical and contemporary sites and examples to illustrate the deep connection between surveillance and what she calls the “enduring archive of transatlantic slavery and its afterlife.” And in her detailing of the rising field of surveillance studies, she finds a remarkable consistency in how surveillance, in whatever period, seeks to extract information from bodies it does not understand, a one-way process of “shedding light” on the racialized “dark matter” that gives the book its title. Students might find her fourth chapter, “’What Did TSA Find in Solange’s Fro?’: Security Theater at the Airport,” especially rich and connective: “If the airport can be thought of as a site of learning, what can representations of security theater in popular culture and art at and about the airport tell us about the post-9/11 flying lessons of contemporary air travel?”

Simone Browne’s Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness is a wonderful book I described at last fall’s conference. Browne takes us through both historical and contemporary sites and examples to illustrate the deep connection between surveillance and what she calls the “enduring archive of transatlantic slavery and its afterlife.” And in her detailing of the rising field of surveillance studies, she finds a remarkable consistency in how surveillance, in whatever period, seeks to extract information from bodies it does not understand, a one-way process of “shedding light” on the racialized “dark matter” that gives the book its title. Students might find her fourth chapter, “’What Did TSA Find in Solange’s Fro?’: Security Theater at the Airport,” especially rich and connective: “If the airport can be thought of as a site of learning, what can representations of security theater in popular culture and art at and about the airport tell us about the post-9/11 flying lessons of contemporary air travel?”

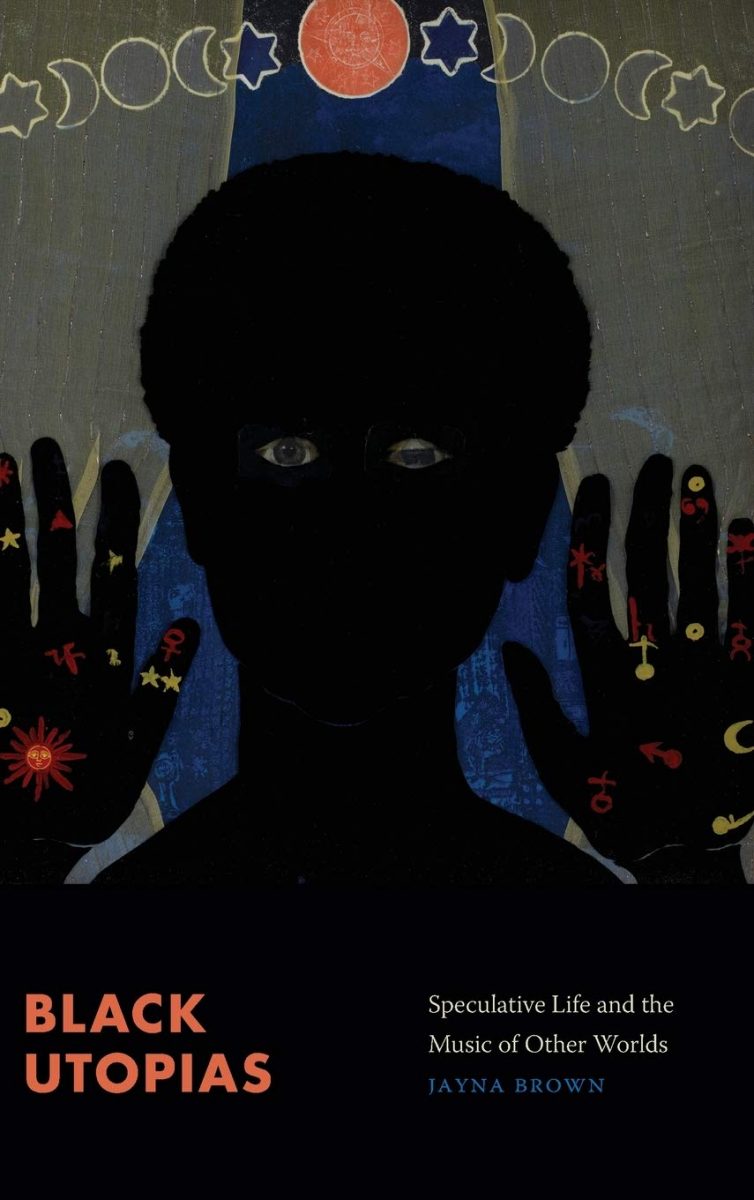

Jayna Brown, who narrates an account of her own father’s life as a self-proclaimed prophet and seer in her book’s preface, presents Black Utopias: Speculative Life and the Music of Other Worlds as a book about radical longing and utopian dissent. In this work that touches on music, science fiction, spirituality, and more, Brown presents and examines the sometimes disturbing speculative visions of Black utopians, including Sojourner Truth, Alice Coltrane, Sun Ra, Samuel Delaney, and Octavia Butler. I was especially drawn to her positioning of utopian thought alongside mystical and radical feminist strains in works that “refuse to attach themselves to the liberal humanist definitions of freedom and equality” (25). She asks instead, through these works, “What happens if we unmoor ourselves from this world?” (156).

Jayna Brown, who narrates an account of her own father’s life as a self-proclaimed prophet and seer in her book’s preface, presents Black Utopias: Speculative Life and the Music of Other Worlds as a book about radical longing and utopian dissent. In this work that touches on music, science fiction, spirituality, and more, Brown presents and examines the sometimes disturbing speculative visions of Black utopians, including Sojourner Truth, Alice Coltrane, Sun Ra, Samuel Delaney, and Octavia Butler. I was especially drawn to her positioning of utopian thought alongside mystical and radical feminist strains in works that “refuse to attach themselves to the liberal humanist definitions of freedom and equality” (25). She asks instead, through these works, “What happens if we unmoor ourselves from this world?” (156).

Tina Campt, in Listening to Images, explains her book’s paradoxical title (and method) as a counterintuitive decision to “listen” to images by noting the value of attempting alternative modes of engagement: “Listening to Images explores the lower frequencies of transfiguration enacted at the level of the quotidian, in the everyday traffic of black folks with objects that are both mundane and special: photographs.” (7) In three short chapters, Campt explores passport photos, early anthropological photos of Africans, and convict photos from the turn of the century. Because these photos of Black lives in precarious situations are staged, compelled, and routinized, they challenge conventional notions of visible resistance or expression. What can we make of what look at first like illegible artifacts or merely functional documents? In exploring the repetition of, for example, the navy blue blazer used in passport photos, Campt seeks “lower frequencies” that tell us more about “quiet soundings” of people navigating paths established by bureaucracy and power.

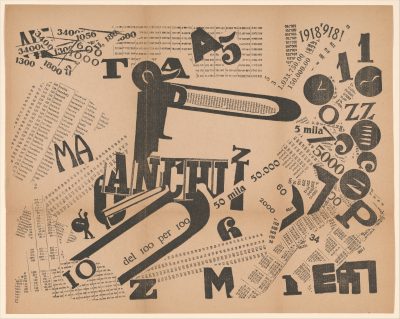

Sometimes my students will tell me I talk too fast. And they’re not wrong. Blame coffee, nerves, my many years spent in New Jersey and New York, or just my usual state of edgy excitement. For whatever reason, I get a high word per minute count when I am teaching. I can promise to try speaking with more measured, spondaic, or prosed deliberation. And yet—and there’s always an “and yet”—there’s something worth considering about the many ways we try to cheat the careful cadence of prepared discourse. In speaking, we often look for ways to thwart the simple left-to-right, top-to-bottom linearity of writing. In simple terms, I think we are looking for ways to say many things at once.

Sometimes my students will tell me I talk too fast. And they’re not wrong. Blame coffee, nerves, my many years spent in New Jersey and New York, or just my usual state of edgy excitement. For whatever reason, I get a high word per minute count when I am teaching. I can promise to try speaking with more measured, spondaic, or prosed deliberation. And yet—and there’s always an “and yet”—there’s something worth considering about the many ways we try to cheat the careful cadence of prepared discourse. In speaking, we often look for ways to thwart the simple left-to-right, top-to-bottom linearity of writing. In simple terms, I think we are looking for ways to say many things at once.